Last year, I completed an edX course on the very (very) basics of economic development. The course – which I found fascinating – inspired me to take a look into the development policy of Japan, a topic I know relatively little about despite studying and reading about the country for a fairly long time. This is a very basic overview of on the history of Japan’s development aid and the role of conditionality in it.

Japan’s development aid: Focus on quality growth and advancement of freedom

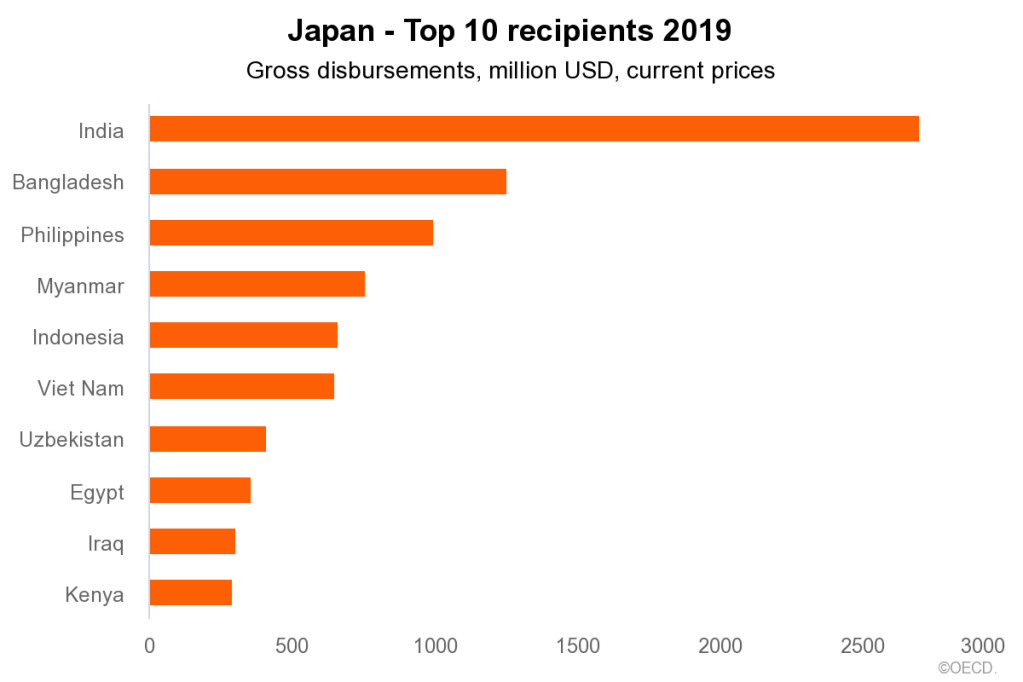

Japan is one of the world’s largest sources of development aid. In 2020 – the latest year for which data is available – the country provided a total of USD 16.3 billion in official development assistance (ODA), making it the fourth-largest donor among OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries. Most of Tokyo’s aid is provided bilaterally, i.e., directly to recipient states, while a fifth of its aid is channeled to multilateral and international organizations, such as various United Nations (UN) agencies.

A factor that sets Japan apart from many other donor states is its widespread use of loans over grants: loans constituted, on average, 56 % of Japan’s aid over the decade between 2009 and 2018. According to Tokyo, this is partly because Japan sees loans as fostering a spirit of “self-help” – i.e., unlike with grants, having to repay the loan will ensure borrowers are incentivised to, for the lack of a better phrase, act better. However, Hitoshi Kato finds another reason for Japan’s preference for loans: they offer a venue for aid disbursement even when government budgets are tight owing to the expectation that the money will come back to Japan’s coffers.

Japan has set three priorities for its aid disbursements. First, the country focuses on quality growth. According to the country’s aid policy-setting Development Cooperation Charter, quality growth means fighting against poverty in a sustainable and inclusive manner over growth that is “merely quantitative in nature.” Such disbursements focus on setting up regulations and institutions and, perhaps most importantly, on developing infrastructure in the recipient country (more on this later). The second focus is on advancing freedom, democracy and respect for human rights by, for example, training civil servants, investing in developing legal systems and boosting anti-corruption efforts. Finally, the third (and quite broad) focus area is on building a “sustainable and resilient” international community, which, in practice, means “taking the lead” on tackling issues such as climate change and, understandably for a country where natural disasters can unfortunately be an everyday occurrence, on fighting against natural disasters.

A quick look at Japan’s actual aid disbursements per sector makes it clear that of the three focus areas, the first takes up much of Japan’s actual aid money: in 2019, a little over half (52.1 %, USD 7.6 billion) of Japan’s ODA was allocated to improving economic infrastructure, with USD 2 billion going into “social infrastructure and services,” a grab bag of a category that includes things such as aid for improving sanitation facilities and boosting education.

Officially, the country’s aid policy is set by Ministry of Foreign Affairs and implemented by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), while other ministries – such as the the Ministry of Justice – are occasionally involved through projects relevant to their field of expertise, such as training judges. In practice, other ministries, too, have a hand in policy and practice of development aid: Outside the foreign ministry, The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) has an interest in promoting economic interests while the Ministry of Finance (MOF) is, naturally, focused on monitoring aid budgets.

A brief overview of Japan’s approach to development assistance

The roots of Japan’s development assistance is in the reparations it was forced to pay to other Asian countries following the country’s defeat in World War II. This past also helps explain the geographical focus for Japan’s aid disbursements, as most of its aid goes to Asian countries. It took until the 1970s for Japan’s aid to get off the ground: and when it did, it really took off: by 1995, it had become the largest ODA donor in the world, and although it has since slipped a few rungs down the ranks of top donors, it still remains one of the largest sources of development aid in the world today.

From the beginning, Japan’s aid/reparations was particularly focused on building infrastructure. Bridges, roads, and railway tracks would be key for spurring economic growth and, through that, development in recipient countries. This would open up opportunities for Japanese firms, too, and Tokyo would often require that the recipient state purchase the goods and services necessary for constructing infrastructure projects from Japanese firms. In the longer run, Japan hoped that the ties built through this process, and the resulting economic growth, would also help develop markets that could buy Japanese goods and while shipping sorely-needed raw materials for Japan’s manufactories.

For Tokyo, this was a win-win: private sector participation in aid projects would provide new markets for Japanese firms’ services and goods while helping integrate Asian economies with Japan’s. Perhaps most notably, this pattern of development aid also aided in the further diffusion of Japan’s own model of economic development, which was built on boosting exports and close cooperation between the state and the private sector, particularly in the form of government subsidies to export industries.

This – supporting economic development abroad while seeking opportunities for Japanese firms to reap the rewards of development – still remains one of the key features of Japan’s aid disbursement. In addition, unlike in the past, nowadays the push for Japanese firms to take part in development projects is no longer limited to just the larger corporations: Japan has in recent years also tried to push small and medium sized firms to also participate in development project, with the aim of opening up and developing new markets for more and more Japanese firms, which would, it is hoped, boost Japan’s sluggish economic growth.

Aid has also been an important tool of foreign policy for Japan. It helped cultivate political ties with countries Japan’s armies had marched across years before. In addition, development aid would become one of Japan’s primary tools for exerting power: unable to throw (or threaten to throw) its weight around in security affairs, aid allowed Tokyo to turn its enormous economy into a tool of foreign policy and diplomacy.

Conditionality and Japan’s aid cooperation

During most of the Cold War era, Japan’s economic growth-focused aid disbursements were largely unaffected by the state of human rights or democracy in recipient states. This was partly due to the desire to advance a win-win model of development aid, where both Japan and the recipient states benefit. But Japan was also highly sensitive to the fact that the roots of its aid were found in reparations, not in selfless “aid” per se. Tokyo’s concern – justified or not – was that trying to prod recipient states towards or tying much-needed infrastructure projects to democratization and respecting human rights would evoke uncomfortable memories of its imperial past among receiving governments.

Human rights began to feature more prominently in Japan’s goals for aid after the Cold War came to an end. Japan first established democratization as part of its aid disbursement criteria in 1992, and further strengthened this goal – with the addition of language stressing the importance of respecting human rights – with its next ODA charter in 2003. As a testament to this newfound spirit, Japan was even willing to shut aid valves in response to what it deemed as unacceptable behavior: Tokyo cut off aid to Sudan and Sierra Leone in 1992 in response to human rights abuses in the former and a coup d’état in the latter, and paused (but later resumed) aid to China following its nuclear tests in 1995.

The importance of democratization and human rights was strengthened further under the 2015 Development Cooperation Charter (essentially, the ODA Charter under a new name), where democratization in particular was elevated into a “priority issue.” While Japan has sought to invest in aid projects that aim to improve rule of law and advance democratization, the monetary amount of such support has remained smaller than most of Japan’s peers.

Most of Japan’s activities in this area focus on government-to-government cooperation in the form of technical assistance to policymakers, supporting the development of legal systems and elections, which, as Atsuko Geiger writes, “are less political and hence less controversial in the view of Japanese aid agencies.” Naturally, the inherent problem in the government-to-government nature of such cooperation also means that the recipient states’ government ultimately decides whether to accept the aid offered or not, and it is somewhat unlikely that authoritarian states would welcome any aid that might foster democratization.

In addition, China looms large in its thinking on how much to push democratization to recipient states. To put it simply, were Japan to really enforce its own guidelines in all cases and suspend aid to authoritarian countries or those backsliding in democracy and respect for human rights, the end result might be that the recipient countries will just get the aid they want and need from Beijing. Japan thus faces the challenge of having to occasionally compete in aid provision with a close neighbor with a far larger budget and fewer, if any, qualms about supporting authoritarian or repressive governments. Thus, while Japan may genuinely wish to support democratization and human rights through its aid provision, it also wishes to balance this with the goal of competing with China for projects and regional influence.

Sources

”Japan” in Development Co-operation Profiles by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2021)

”Cabinet decision on the Development Cooperation Charter” by Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (2015)

”Japan-East Asia Economic Relations” in Japan’s international relations: politics, economics and security by Glenn D. Hook, Julie Gilson, Christopher W. Hughes and Hugo Dobson, Routledge (2012)

”Values vs. Interest: Strategic use of Japanese Foreign Aid in Southeast Asia,” by André Asplund (2015)

”Japan’s support for democracy-related issues – Mapping Survey” by Atsuko Geiger, Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) (2019)